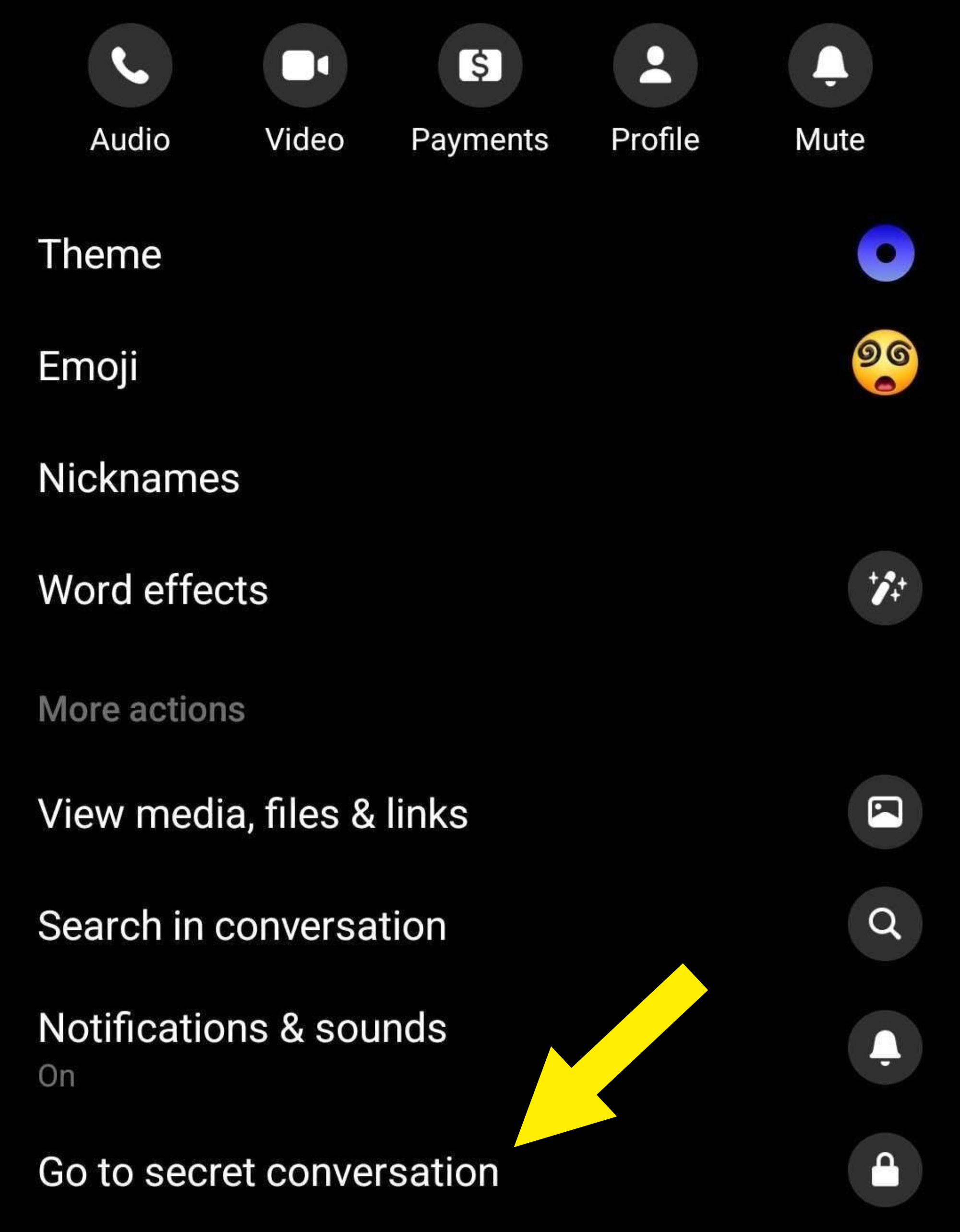

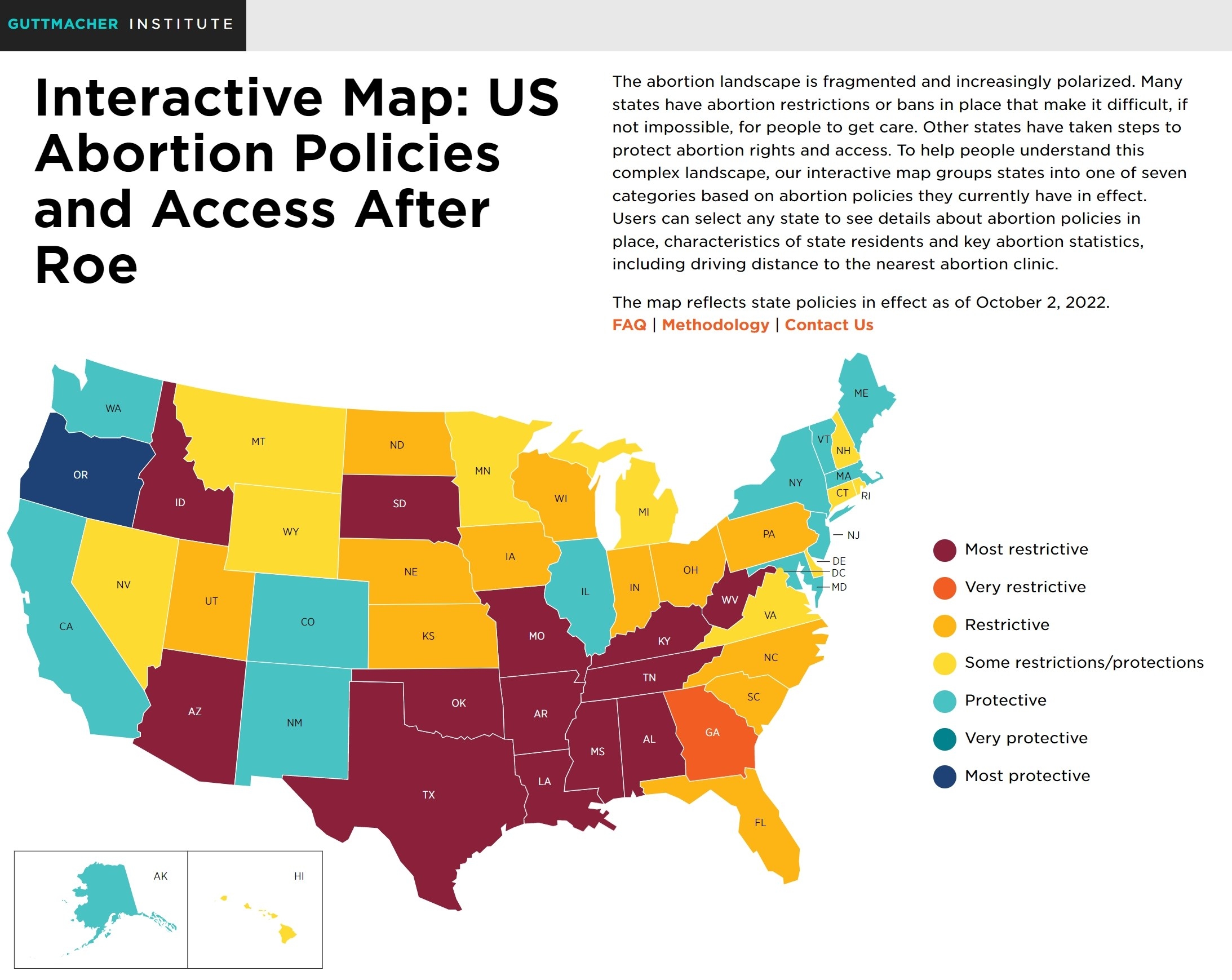

Similarly, it’s less likely that law enforcement officers would know to subpoena data from your period tracking app. “They have to have reasonable suspicion in order to issue that subpoena or court order to get your data,” Bethany explained. “Where are they going to find that? It’s likely going to be more mainstream channels, like social media and Google searches.” To give you a better idea, between Jan.–June 2021 in the US, Google received more than 50,907 government requests for user data and produced data for 82% of requests, while Meta received more than 63,657 government requests for user data and produced data for 89% of requests. For a real-life example: In 2019, the FTC filed a complaint against Flo for misleading users after the Wall Street Journal reported that the period tracking app had been sharing users’ data with marketing and analytics firms, including Facebook and Google, despite Flo’s privacy policy stating it wouldn’t send such information to third parties. “Flo could have legally sold data to Facebook if it had just said that in its privacy policy. It was the fact that it said it was not dealing with that express action that got it in trouble with the FTC,” Bethany explained. Beyond femtech, HIPAA-covered entities — like your healthcare provider with whom you share your medical history — can still be subpoenaed. “A lot of people don’t realize there’s a permissible disclosure in HIPAA for law enforcement and court orders. So, technically, if your provider got a subpoena to turn over your data, they could do it lawfully,” she added. On that note, in recent years, Facebook Messenger has begun offering an encrypted messaging feature that users can opt in to for individual chats. You can activate encrypted messaging per chat by selecting the “i” icon in the top-right corner, and then choosing, “Go to secret conversation” under the “More actions” section. If you’re curious about how data can be deidentified and reidentified, consider the data that an app could collect about you: name, birthdate, address, email, phone number, geolocation, gender, etc. Obviously, data like your name or address could directly identify you, whereas data like your zip code or gender could indirectly identify you. By scrubbing certain identifiers, data can be anonymized, and indirect identifiers — though ambiguous separately — can reidentify users when properly combined. These protective laws are in stark contrast to “bounty hunter laws,” such as Texas’s Senate Bill 8 (SB8 for short). Passed in 2021, it incentivizes citizens to sue anyone who’s helped someone have an abortion by rewarding them a cash “bounty” if they win. SB8 has inspired similar laws in Idaho and Oklahoma. You can find state laws around abortion via the Guttmacher Institute’s State Legislation Tracker here and their interactive map of US abortion policies here. “It’s because there’s so much information in there that somebody can go and use to steal your identity. You can’t change your health data like you can change your credit card number,” Bethany explained. And with states banning abortion, the value of health data has skyrocketed. And while limiting the data you enter into a period tracking app may provide a greater chance of privacy, the apps naturally work best and make the most accurate predictions when you provide more information.